Personal Graphics Drawing Library

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been looking into the possibility of creating my very own Graphics Library. One of my favorite areas of Game Development is how code is structured in the architecture of the game. In my studies, I have spend a lot of time learning how best to program Game Architecture, while optimizing memory and the speed of your program. Through all of my time writing decoupled code, I have always used some sort of Graphics Library that was publicly accessable from the Internet. When I first studied Game Arcitecture, I initially used Allegro, and more recently, I have been exploring a library called RayLib. Recently, this has sparked my interest to create a library of my own. For me, it is tons of fun to dive in to lower level code and explore all that I have access to adjust or manipulate. For this project, I decided to explore Win32 API.

Starting my research, I was a little bit overwhelmed looking at the documentation that is present for this system. This is partially due to the high amount of typedef used throughout the API as well as their programs following a different flow and entry point than that I am used to. For all of my work thus far (aside from my work in Unity and Unreal), I have been mostly been working with console based programs. The Win32 Documentation however uses an Application based entry point, one that I am unfamiliar with. Using their examples, I was able to get a static white window open, but immediately went to work on implementing the same window within a console context. The first challenge was figuring out how to get the program handle, which is passed in as a parameter in the Application entry point and is requird to open a window, but with a litte bit of digging, I discovered a function that finds this handle. With the console now availible, this allows me to use it for debug purposes throughout development, while also being able to display a game window.

After sorting out that issue, my next challenge was taking the window code and abstracting it into its own class that I named the GraphicsSystem. This was a challenge because when opening the window, the funciton requires you to pass a function pointer where you are handling all of the messages that is sent for the window to process. Upon abtracting the class, however, Intellisense swiftly reminded me that you cannot pass member functions into a non-member function outside of the context of the class. Luckily though, I was able to find a solution! By making this function static, and any other dependency functions static, it solves this issue, but removes the ability of those static members being able to access any member data. To solve this, I made the GraphicsSystem a Singleton, which allowed any static function able to access data local to the singleton.

After finishing the abstraction, I led the charge into research about Bitmaps, and how I can load bitmaps from a file into the window that I have on screen. Through this process, I was quickly able to implement basic drawing functions to create shapes, but once I got into bitmaps, I realized that I was in WAY over my head. The process to load Bitmaps in the Win32 API is very convoluted. To load a bitmap, you have to call functions from the Windows Imaging Component API to load the bitmap, then convert it to the Direct2D Bitmap which doesn’t have file loading functions natively within. Regardless, with hard work, grit, and hours of scrolling through documentation, I was able to load and draw a bitmap on screen!

Here’s a sneak peak at what some of my drawing functions looked like:

void GraphicsSystem::flip()

{

pRenderTarget->EndDraw();

pRenderTarget->BeginDraw();

}

void GraphicsSystem::drawEllipse()

{

PAINTSTRUCT ps;

BeginPaint(windowHandle, &ps);

pRenderTarget->Clear(D2D1::ColorF(D2D1::ColorF::SkyBlue));

pRenderTarget->FillEllipse(ellipse, pBrush);

EndPaint(windowHandle, &ps);

}

void GraphicsSystem::drawGraphicsBuffer(GraphicsBuffer* gb, float locX, float locY, float scale)

{

float height = gb->mpD2DBitmap->GetSize().height * scale;

float width = gb->mpD2DBitmap->GetSize().width * scale;

pRenderTarget->DrawBitmap(gb->mpD2DBitmap, D2D1::RectF(locX, locY, locX + width, locY + height), 1.0f, D2D1_BITMAP_INTERPOLATION_MODE_LINEAR);

}

With this system in place, I put together a small game loop to exist within the main function to test out the functionality of these drawing functions. Ideally, this game loop would be abstracted into it’s own Game class.

int main()

{

GraphicsSystem::initInstance();

GraphicsSystem* gs = GraphicsSystem::getInstance();

gs->init();

cout << "Well Well" << endl;

GraphicsBuffer* buf = new GraphicsBuffer(p);

bool shouldContinue = true;

while (shouldContinue)

{

shouldContinue = gs->update();

gs->drawEllipse();

gs->drawGraphicsBuffer(buf, 600, 300, 0.25f);

gs->flip();

}

system("pause");

//delete buf;

//buf = nullptr;

gs->cleanup();

GraphicsSystem::cleanupInstance();

}

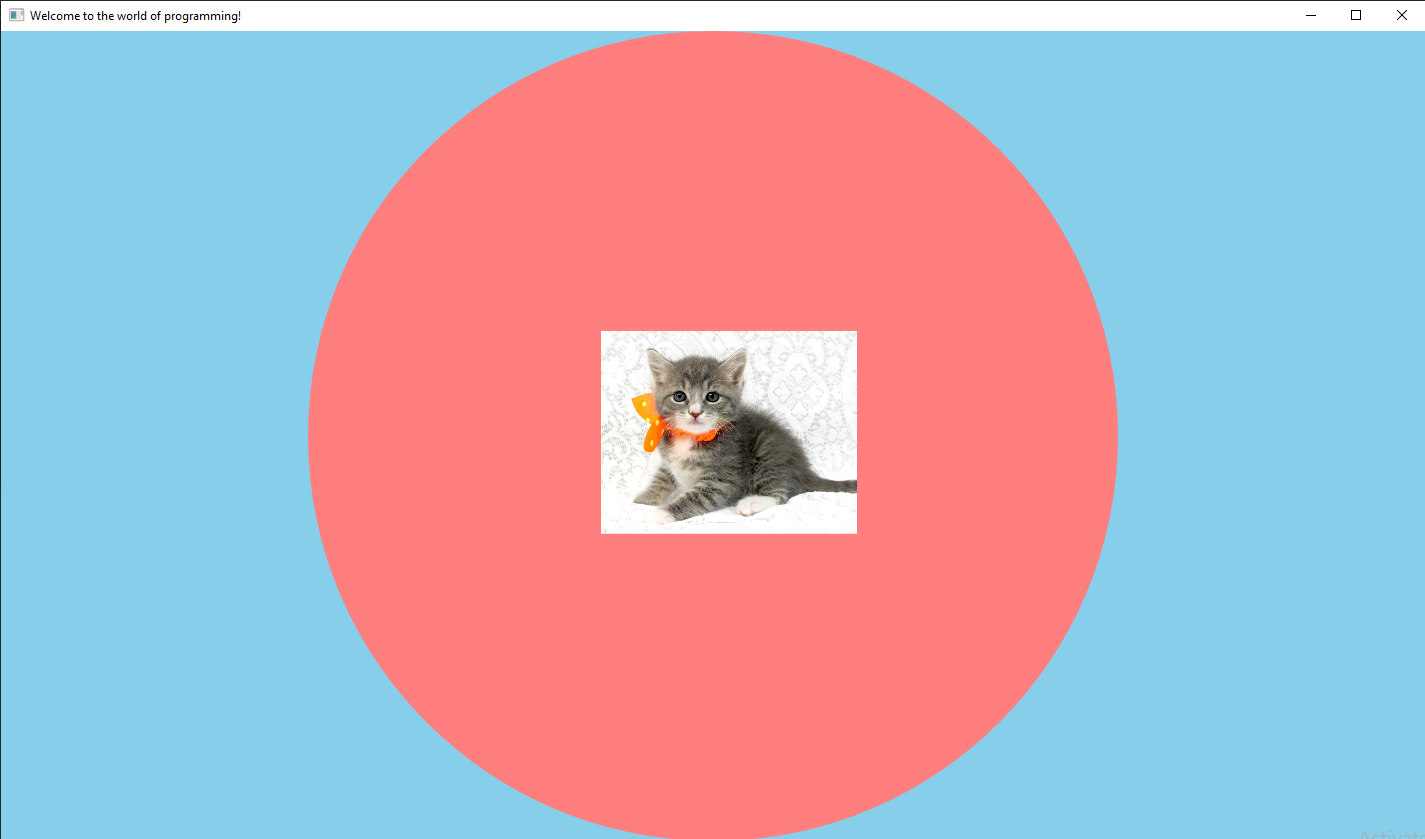

And with all of the pieces in place, I obtained the final output shown above!

After 3 weeks of work, I ended up with a product that I am very proud of! Visually, it doesn’t look like much, but Game Architecture is the foundation that Video Games are build upon, and as every house is as strong as its foundation, every game is as impressive as the architecture that it was built upon. Poorly build architecture can lead to cracks in the game, possibly plummeting performance. However, finely tuned architecture can enable Game Developers to do their jobs at the highest level, granting a rich and wholesome experience to the consumer on the other end.

Reflecting on this project, there is so much more that could be done! While working on this project, I was able to abstract a lot of data, but there is still a lot more abstraction that could be done. For example, the drawEllipse function could accept parameters to draw different ellipses, rather than the hardcoded one in. I could’ve expanded the GraphicsBuffer and created a Sprite class, which could point to a small section of the GraphicsBuffer. Doing this would give me more control of the lower level code than what I had in Allegro or RayLib, and while this makes it much harder and time consuming to figure out how to best carry out these game tasks, it gives you a lot more flexibility if you were working in a personalized environment suited to the game that you were developing.